Recently, I was taking care of a gentleman in his sixties with high blood pressure and diabetes. My goal, I explained to him, was to prevent a heart attack or stroke which are too frequently the consequence of these diseases. I will closely monitor his kidney function and blood sugar levels so that I can recommend the safest and most effective medications for him so that he can live as long and symptom-free as possible. This medical care is based on the latest medical evidence and guidelines, and I am proud to provide it.

If I am to truly be a steward of his health, however, it is not enough to focus on his medical care. I must also carefully consider the greater social context of his life. Reducing consumption of refined carbohydrates and sugar is crucial to blood sugar management in patients with diabetes. Are fresh fruits and vegetables still affordable to him or is he mostly eating cheap processed foods to stretch his grocery budget? For this patient, insulin was necessary to prevent painful neuropathy in his hands and feet. How much are the copayments on his insulin? Is he taking the full recommended dose, or is he cutting back because of expense?

Understanding these social determinants of health is a core competency of high-quality medical care in the twenty-first century. Given that the majority of premature death is attributable to factors other than medical care, I would be remiss as a primary care provider if I didn’t engage with the social and environmental factors that bring illness into my patients’ lives.

One harmful social condition that I must engage with every day is the commercial health insurance system which mediates access to medical services. In this system, insurance companies collect enormous amounts of money through premiums in exchange for limited access to doctors and medications only after you additionally pay co-pays and meet your deductible.

The expense of co-pays and deductibles all too often push those with chronic illnesses into poverty. Nearly half of the people diagnosed with cancer end up with negative net worth in the subsequent two years. Every year in America 530,000 people file for bankruptcy in part due to medical debt. Many find themselves being sued by hospitals when they struggle to keep up with their bills.

I see this damage done by our current commercial insurance system every single day. I see how poverty leads to disease which requires medical treatment which then exacerbates poverty and the cycle begins anew. It’s enough to drive you to despondency.

But let me tell you, I’m not despondent at all. In fact, I’m quite hopeful.

I’m hopeful because there is a presidential candidate who is working to break this cycle of illness and poverty. There is a candidate who believes that health care is a human right. There is a candidate who believes that no one should be impoverished by illness or made ill by the deprivations of poverty. There is a candidate who is fighting for my patients, for me, and for you.

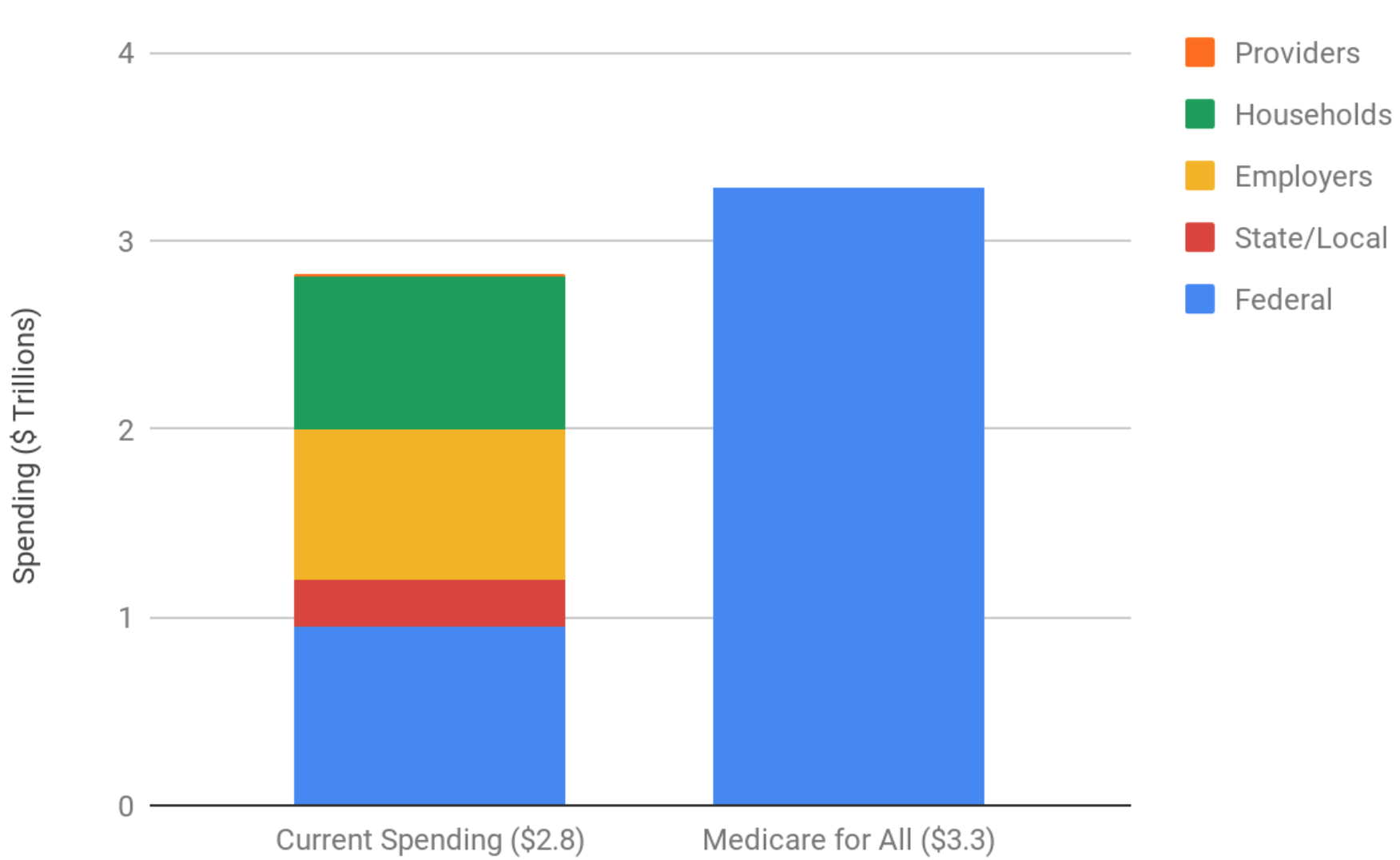

That candidate is Bernie Sanders and his plan for Medicare For All will put an end to the financial destructiveness of our current health care system. By providing a universal, comprehensive health care benefit that is free at point of service for all Americans, we can finally have the health care system we deserve in this country.

As a primary care doctor, I can think of no better advocate for health and well being of my patients than Bernie Sanders and I am proud to join Doctors For Bernie in endorsing him for the democratic nomination.