A little over a year ago, I made my personal case for Medicare For All. In that post, I argued that the American health care system has intolerable financial toxicity on patients and that a transition to a single payer system, such as Medicare For All, was the only feasible way to achieve true universal health care coverage in which a person’s economic status was not the main determinant of the health care they receive.

Since then, Medicare For All has continued to gain momentum with many of the leading contenders for the Democratic presidential nomination like Bernie Sanders, Elizabeth Warren, Kamala Harris, Cory Booker, and Kirsten Gillibrand explicitly in favor of this approach.

Pramila Jayapal (my very own congressional representative) has released an updated house bill (H.R. 1384, summary here) with 108 cosponsors, to implement Medicare For All. This operates as a companion bill to Bernie Sanders’ Medicare for all bill (S.1804) with 16 cosponsors in the Senate.

As coverage has increased, I’ve seen some important points about Medicare For All go missing from the popular discourse, so I would like to highlight a couple of points here.

What will the quality of coverage be like?

Although I feel that overall “Medicare For All” is a great slogan, it sometimes creates confusion because many assume that this means that the current Medicare plan would simply be extended to all Americans. However, the Jayapal and Sanders bills both outline a heath insurance payment system that is far more generous than current Medicare. For that matter, it’s far more generous that most commercial insurance. We’re talking no copays, no deductibles, unlimited network, vision benefits, dental benefits, and long-term care benefits. For the patient, this means that if the health care is medically indicated there are zero financial barriers to you receiving it.

How are we going to pay for it?

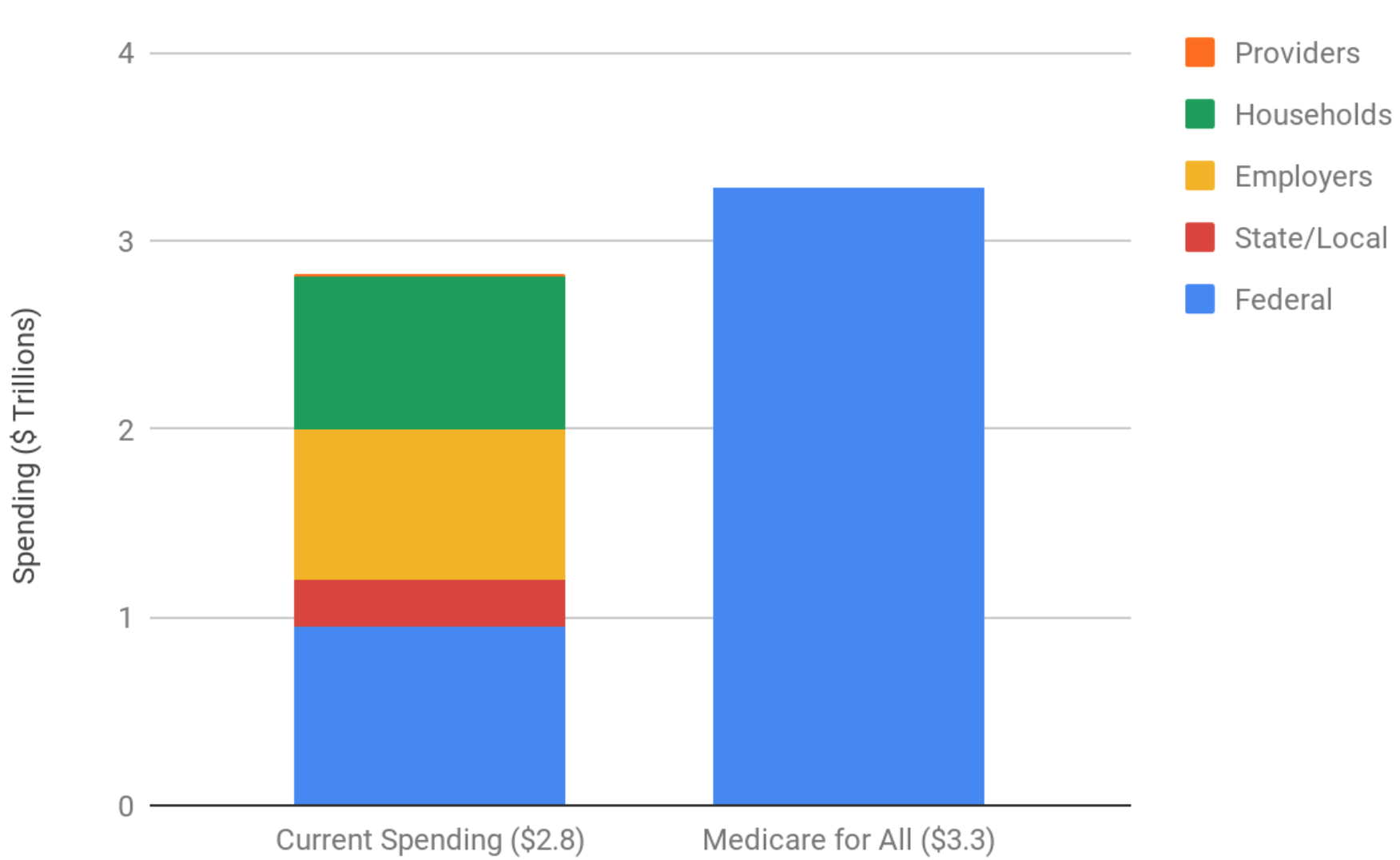

Many commentators have brought up that the budget allocation for a Medicare For All bill, by nature of paying for all Americans’ health care, is quite large. However, when compared to current national health care spending, the increase is marginal. For example, using estimates from The Urban Institute, annual health spending would increase from $2.8 trillion per year to $3.5 trillion per year.

That additional $500 billion gets 34 million more Americans medical coverage, 75 million more dental coverage, and 167 million more vision coverage. That is in addition to upgrading every American’s health care coverage as described above. There are a variety of ways to pay for this including repealing Trump-era tax cuts ($230 billion per year) and implementing a wealth tax ($275 billion per year). Matt Bruenig has also laid out how to capture current employer health insurance spending through payroll taxes.

Advocacy versus legislative action

It’s worth emphasizing that Medicare For All is still in the advocacy stage, not in the legislative stage. Although a majority of Americans already support Medicare For All, activists and advocates are working to build upon that strong momentum and build enthusiasm amongst legislators who can bring Medicare For All into reality. Not every nitty gritty detail is going to be exactly worked out at this stage and that’s okay. Good quality legislation takes time to build and refine. It often requires ongoing amendment after passage. We as a nation have proven ourselves capable of this in the past and we can continue to be capable of it as long as we remain committed to universal, comprehensive health care coverage that is free at point of service.